|

Colt Model 1903 Pocket Hammerless .32 ACP serial number

966061 - OSS / CIA issued military contract pistol outside the known and

established serial number range. The highest recorded production

number is 572215, with serial numbers 572216 through 572451 being

manufactured but never assembled, being scrapped in 1945.

Seven serial numbers numbers higher than the highest known number on this

model have been observed. 831093, 831215, 831242, 831289,

831291, 966061 and

966071. Two of the pistols

that are identified by John Brunner in his book on the Colt Pocket

Hammerless Models (831093 and 831242). Four of the seven are known to have had their

original serial numbers removed along with other government markings and

were marked with a serial number that could not be traced to the U.S.

Government. Colt Model M .32 serial number 966061 was issued

to Lt. Col. Alexander Sogolow (also spelled Sogolov), a Russian born

CIA agent stationed in Germany following WWII. Accompanying the gun is

a modified unmarked shoulder holster as well as documentation. This

pistol has all the military characteristics of a war time manufactured Model

M .32 pistol.

Right side of Colt 1903 Pocket Hammerless serial number

966061. Note lack of U.S. PROPERTY mark.

|

Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Sogolow |

| Born: 9 February 1912 |

Russia |

| 1947 |

Munich, Germany |

| 1968 |

U.S. Government Official

Headquarters, U.S. Army element, Joint OPS Group, R.1B 945, The Pentagon |

| Died: 19 January 1982 |

Burial: Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington,

Virginia

Plot: Sec: 59, Site: 2608 |

|

Alexander Sogolow - Obituary, January 23, 1982

Alexander Sogolow, 69, a retired Army lieutenant colonel

and senior intelligence officer with the Central Intelligence Agency,

died of respiratory failure Tuesday at the National Naval Medical

Center. He lived in Chevy Chase.

Col. Sogolow was a native of Kiev, Russia. He came to this country in

1926 and settled in New York City. He was a 1936 graduate of the City

College of New York and attended St. John's University law school in

Brooklyn.

He served with the Army in Europe during World War II. He was an

intelligence officer for the U.S. High Command in Berlin and a Russian

and German interpreter for senior allied officers, including Generals

Eisenhower and Patton. He left active duty in 1948 as a lieutenant

colonel and joined the Army Reserves, from which he retired in 1972.

Col. Sogolow joined the CIA in 1949 as an intelligence officer in

Germany. During his years with the agency, he lived in Washington and

Germany. Since 1963, he has lived in Washington and Chevy Chase. He

retired in 1972.

He was a member of the Association of Former Intelligence Officers, the

Central Intelligence Retired Association, the Retired Officers

Association and the American Association of Retired Persons. He was a

volunteer for the American Red Cross.

Survivors include his wife, Phyllis, of Chevy Chase; a daughter, Terry,

of Silver Spring; a son, Robert, of Van Nuys, Calif., and a sister,

Tamara Weinschenker of New York City.

The family suggests that expressions of sympathy be in the form of

contributions to the American Heart Fund or to the American Cancer

Society. |

Close up of serial number 966061. Style is different

that that of serial numbers applied at Colt.

There is no ordnance mark present behind the thumb safety.

Unmarked shoulder holster that accompanied Model M .32 sn

966061 (front view)

Unmarked shoulder holster that accompanied Model M .32 sn

966061 (rear view)

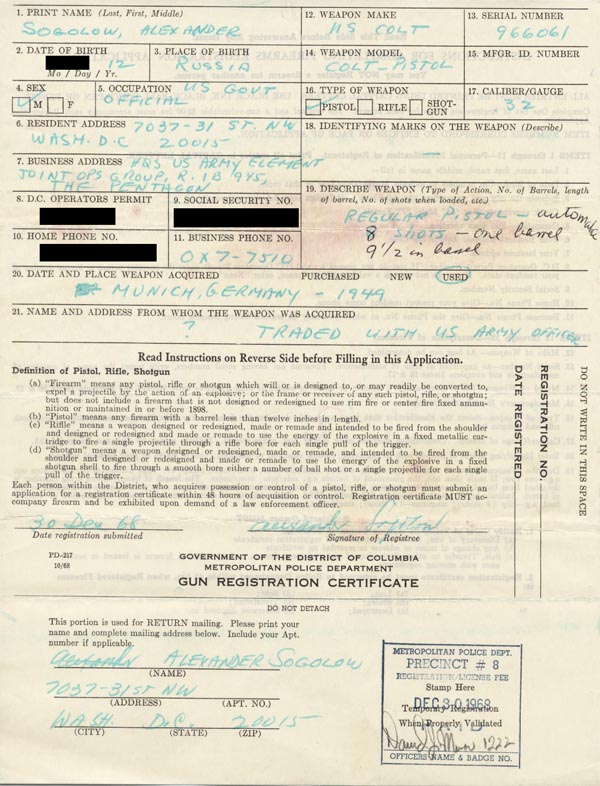

Alexander Sogolow's Gun Registration Application for

Colt

Model 1903 Pocket Hammerless .32 966061 dated December 30, 1968.

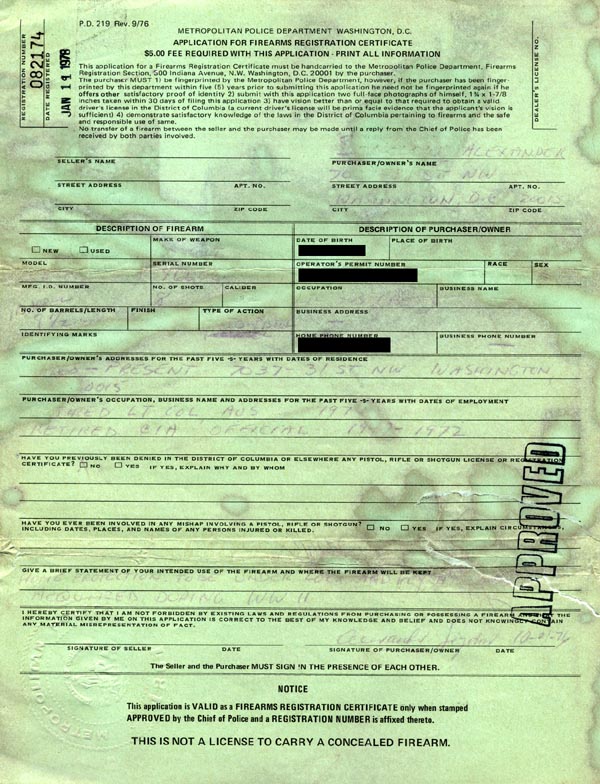

Alexander Sogolow's Gun Registration Application for

Colt Model 1903 Pocket Hammerless .32 966061 dated October 21, 1976,

but not approved until January 19, 1978.

MOLEHUNT - THE SECRET SEARCH FOR TRAITORS THAT SHATTERED THE CIA

(c) 1992 by David Wise

Excerpt from Chapter 12: Molehunt

"There were others, many others. One of those placed under the

counterintelligence microscope was Alexander Sogolow, a large and boisterous

Russian-born case officer from Kiev who had the misfortune to be known

throughout the agency by the name Sasha.

It was Sogolow whom Peter Karlow had been thinking of when the polygraph

operator asked him about "Sasha," making the needle jump and putting Karlow

deeper into the quagmire. In Russia, many names have diminutives,

affectionate nicknames that friends and family use in place of the more

formal given name. For Alexander, the diminutive is always Sasha.

Assigned to headquarters in the early 1960s after a tour in Germany, Sogolow

got wind of the fact that the mole hunters in Langley were looking for

"Sasha." On a trip to Vienna, he unburdened himself to Kovich, who was then

serving in the Vienna station.

"They're going to come after me," Sogolow bemoaned. "I'm in trouble. They

say his name is Sasha."

"Hell," Kovich assured him, "relax. There are eighteen million Sashas in the

Soviet Union." Ironically, it was the first that Kovich had heard about the

search for penetrations back at headquarters. He didn't know that he himself

was a suspect.

Sasha Sogolow was born in czarist Russia in 1912, the son of a wealthy

Jewish businessman who supplied uniforms for the Russian army. Sogolow used

to tell the story of how, when the revolution came, the family fled to

Germany, their jewels hidden in a toy cane that was given to him. The family

made it safely to Germany, but little Sasha lost the cane. At least that is

how Sogolow liked to tell the tale. [15]

The Sogolows immigrated to New York in 1926, where Sasha graduated from City

College and St. John's University Law School. It was the Depression, and

Sogolow, according to a CIA colleague, "worked for a while selling

chicken-plucking machines, until he was beaten up by a bunch of manual

chicken-pluckers." [16] During World War II, he was an Army intelligence

officer, acting as an interpreter for General Eisenhower and General Patton,

and then working for the High Command in Berlin. Rejoined the CIA in 1949

and was sent to Germany.

Since the Soviet Union was the main target of the CIA, the agency needed

Russian-speakers. Like Sogolow, many officers in the Soviet division

inevitably had Russian backgrounds, which to the mole hunters made them all

the more suspect.

And Sogolow, despite Kovich's ironic reassurances, was under suspicion by

the SIG. He had a Slavic background and had served in Berlin. It was true

that his name did not begin with the letter K, but by now, the CI Staff was

not wedded to that detail of the mole profile. The search for penetrations

had begun to spread to other letters of the alphabet.

Worst of all for Sogolow, his name was Sasha. On the face of it, it seemed

unlikely that the KGB would use the code name Sasha for someone who really

was called Sasha. But it was not impossible, and in the atmosphere of the

time, the CI Staff was leaving nothing to chance.

"We looked at his file," Miler recalled. "We went over operations he was

involved in in Germany, where he had been." The SIG, Miler said, was

particularly interested in Sogolow's "proximity" to Igor Orlov, a

Russian-born CIA contract agent who had worked for Sogolow in Frankfurt in

the late 1950s, and who was emerging as the

newest suspect.

As for Sogolow, Miler said, "nothing was found." He was not transferred to a

lesser job, Miler insisted, nor placed in the limbo that awaited other

targets of the mole hunters in the D corridor. But Sogolow was never to

reach the level he had hoped for within the agency."

[15] It made a nice story, but it seemed improbable that the jewels would

have been entrusted to a five-year-old. Within the Sogolow family, the

accepted version was that the jewels had been smuggled out of Russia in the

heel of the shoe worn by Sasha's older sister.

[16] David Chavchavadze, Crowns and Trenchcoats: A Russian Prince in the CIA

(New York: Atlantic International Publications, 1990), p. 154. |